By Gyorgy Busztin

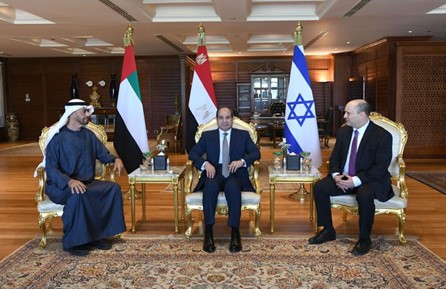

No sooner had his two guests said farewell to Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi of Egypt on the tarmac of Sharm el-Sheikh airport than speculation began about a new triple alliance being forged between Egypt, the UAE and Israel.

It might have escaped the attention of many that the three leaders’ meeting took place on 21 March. But Iran would certainly have taken note: Nowruz, the Persian New Year, fell on the same day. For Iranians, Nowruz marks a new beginning, a time to make new vows, and forgive grudges.

In a sense, the leaders of the three countries who met in Sharm el-Sheikh abided by the first two traditions, by forming a new front of unity against Tehran. More importantly, however, they did not forgive grudges: To Israel, and a lesser extent, the UAE, Iran is still seen as an existential threat.

The timing may have been symbolic, but was probably prompted by circumstance. Iran and the P5+1 interlocutors in Vienna have inched closer to reviving the JCPOA. Reportedly, only a single issue remains in the way of success, but it is a significant one – the removal of the United States’ designation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist entity. Neither Israel nor the Gulf countries want this to happen, and the leaders who met in Egypt may have been mounting a last-ditch effort aimed at dissuading the US from acceding to this, or, at the very least, to prepare for the worst together.

It is worth mentioning that attitudes have changed somewhat since the JCPOA was first signed. The spectre of a nuclear Iran is now deemed a bigger threat than that of an Islamic Republic freed from the grip of maximum pressure sanctions.

This, and the backdrop of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, was the reason the three countries met for what is, for all intents and purposes, a co-ordination of strategies.

A cursory look at their respective concerns can explain what brought them together.

Both Israel and the UAE have ample reason to be concerned about a post-sanctions, re-energised, and assertive Iran. The Islamic Republic may shed its nuclear ambitions in exchange for an end to crippling sanctions, but will never renege on what it sees as its mission of being the uninvited protector of all Shia of the Middle East, foremost among them the “Axis of Resistance” countries, which Tehran considers its own turf.

Israel is locked in a war of attrition with the Islamic Republic, one which both sides barely bother to keep secret. Last month, Israel carried out a major strike against a drone factory in Iran. Tehran has hit back in a fairly-restrained manner – for fear of disrupting the Vienna talks – but sent a loud and clear message all the same. In unleashing missiles against Erbil barely two weeks ago, Tehran was expressing its displeasure with the Kurds – who are seen as being too close to Israel and the US – and the Iraqi government, which is trying to wriggle free of Iran’s suffocating grasp.

The UAE may not have similarly pressing reasons to fear Iran, but it feels the heat from Tehran’s proxies, the Houthis, who keep targeting its cities and oil installations via drone attacks, which have clearly unnerved Abu Dhabi. The attacks give the lie to the image of stability the UAE is trying to project in order to sustain its role as regional commercial and energy hub, and to attract foreign investment and talent. Such strikes are also a stark reminder that Tehran can always put pressure on neighbours via proxies without the danger of being taken to task. This is an unsettling prospect for the blossoming romance between Abu Dhabi and Jerusalem in the wake of the Abraham Accords, a partnership Tehran has squarely declared it will not tolerate.

Both Israel and the Emirates, demographic dwarfs, can benefit significantly from being tied to a Sunni Muslim powerhouse. With a population about to exceed 100 million, Egypt is the only country in the region that qualifies to be a counterweight to Iran. Modern warfare is no longer reliant on numbers, but Gulf countries exposed to Iran may feel that a benevolent Egypt would be a welcome backstop in times of trouble.

But where does this all leave Egypt? Thankfully distant from Iran, it does not have to fear the direct impact of any displeasure with its policies from Tehran. The two are in a nexus of sorts that neither puts on display, even though Iran’s reformist presidents have tried time and again to portray the relationship as one connecting two Islamic superpowers. Differences (Israel, Gaza Palestinians, Syria) aside, both sides strive to portray relations as normal, even cordial. The Islamic Republic has looked the other way when Egyptians reacted violently to attempts by Iran-sponsored Shi’a clerics to proselytise – if the expression holds – in an almost exclusively Sunni Muslim country.

Egypt’s concerns are thus not Iran-driven, but it can benefit from teaming up with Israel and the Emirates. For Cairo, the chief national security concern is Ethiopia. The dam-colossus on the Nile that Addis Ababa is completing may leave Egypt with dangerously low water levels. Only strong international pressure can dissuade Ethiopia from blocking the river’s flow and leaving the “Gift of the Nile”, as Herodotus described Egypt, on the brink of thirst and starvation. Egypt may benefit from a quid pro quo with the UAE and Israel: In exchange for a firm commitment of support against Iranian threats, it could receive assurances on water and grain.

Since the campaign to liberate Iraqi-occupied Kuwait, Egypt has studiously avoided being drawn into active Arab internecine conflicts, or other regional calamities. It managed to avoid being sucked into the Libyan war on the side of the UAE, and did not enter the Yemen conflict, despite Saudi Arabia’s wishes. Internal concerns committed Cairo to an inward-looking policy. But current transformative events – the likely end of the sanctions on Iran with a revived JCPOA, and the ongoing Ukraine war – compel it to take a more active role. This may be at the root of its new activism, and its engagement with Israel and the UAE.

The ultimate motive here may be Egypt’s fear that with the price of grain spiking – and perhaps reaching unprecedented levels with two major producers locked in conflict in Ukraine – it will be unable to feed its burgeoning population. The price of aish, the Egyptian flatbread, has traditionally been a make-or-break factor in local politics. (Bread in Egypt is heavily-subsidised, which puts a major strain on its economy). How it would contend with a prolonged grain shortage that drives prices higher and higher on the world market is anybody’s guess, but it is a very plausible reason Cairo is looking for Emirati largesse.

Israel, which is highly unpopular with the Egyptian public, is nevertheless a contributor to the country’s economy through the joint gas project the two operate together. Gas extracted by Israel is liquified in Egypt, and is now a hot commodity as Europe attempts to reduce reliance on Russia.

Demographic weight in exchange for economic perks seems a fair deal for Egypt. As a pioneer of Arab-Israeli rapprochement, nobody can reproach Cairo over not opting for more. By providing just a photo opportunity, President Sisi did his two guests a great favour.

Image caption: President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi of Egypt (C) hosted a summit with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed Al Nahyan of the UAE (L) and Israel’s Prime Minister Naftali Bennett (R) in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, on 21 March 2022. Photo: Israel’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

About the Author

Dr Gyorgy Busztin is Visiting Research Professor at the Middle East Institute, National University of Singapore.

A career diplomat and an academic, he served, between 2001 and 2011, as Hungary’s ambassador to Indonesia and subsequently, Iran. In 2011, Dr Busztin was appointed deputy envoy of the United Nations in Iraq, responsible for the political, analytical, electoral and constitutional support components of the UN’s mission in Iraq. He served at the level of assistant secretary-general until October 2017.

Dr Busztin holds a degree in Arabic history from Damascus University, Syria and a Doctorate in Arabic language and Semitic philology from Lorand Eotvos University in Hungary. In addition to his native Hungarian, he speaks English, French, Arabic, Farsi/Dari (Persian), Malay (Indonesian) and Russian. He believes strongly in political and intercultural dialogue and has engaged leading politicians, intellectuals, religious leaders and representatives of civil society.